|

When Shin was born, the river and its tributaries flooded their banks, but because the town was above in the semi-arid highlands, no lives or farmlands were threatened. His mother, who had suffered greatly through his birth, lingered for three days, then died in a great pool of her own blood, never recovering to hear the name he was given. His father, to commemorate his birth, and to memorialize his wife, bought a hardstone vase with a phoenix in flight, and placed it near the ancestral shine in alcove by itself.

[Chinese, carved green and brown hardstone covered vase with phoenix and loose ring designs, wood stand] None of the family had guessed, the depth of his father's feeling for his new wife, and was touched that he had placed a slip prunus branch in the space around the vase's wooden base.

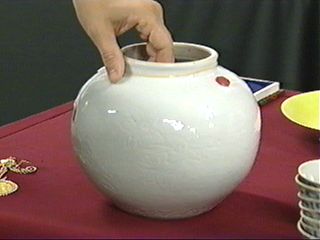

[Chinese, late Ming Dynasty, Blanc-de-Chine porcelain bowl with slip prunus branch designs (small rim chip), 17th Century] But, when he buried her with the two small pottery bowls, which she had brought as her dowry, and the four intricately designed bronze bracelets that she wore every day, they objected. [Group of six, ancient Ban Chiang objects: two small pottery bowls and four Middle Period bronze bracelets (flaws and repairs)]

"Why bury these valuable objects with the deceased?" his fathered asked.

"She was only a young wife, his mothered pointed out.

Shin's father reminded them: "She has given me a son."

Shin's home was a large farmhouse with hard packed earthen floors of rectangular shape, and large wooden poles holding up the center ridge of the roof, and smaller ones supporting the sides of the gabled eaves.

[Chinese, Han-style painted pottery model of a farm house/barn (repair)] The roof was thatched, and under it lived the family, and below them, their stock of goats, chicken, sheep and pigs, and the oxen and the horse. [Group of four, well-modeled, Chinese Han Dynasty, pottery models of pigs of various sizes (possible minor repairs to two), one with some original pigments remaining] There were three generations living together in that old house: the grandparents, his father, the older uncle's, and their wives and children, as well as their ancestral spirits, which they nourished in the form of food offerings and burnt incense.

Shin's grandfather was the district's head civil servant, and was respected for his Confucian scholasticism.

[Pair of antique and finely detailed, Chinese ink and color on paper ancestral scroll paintings: a seated elderly official with pleasant facial expressions and his wife wearing red robes and an elaborate headdress (some minor old flaws to both), both 19th Century; well re-mounted] Shin aspired to be the same, and studied very hard every day to increase his proficiency; never playing outside and throwing stones on the fish among the water reeds, or battling with wooden swords, the phantom enemies on horseback.

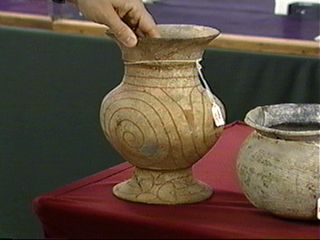

[Large, Chinese Yuan-style blue and white with copper-red porcelain charger with fish amid water weeds motif, surrounded by lotus and diaper bands (hairline)] When Shin concluded his studies and his teachers established he knew enough about Confucianism to be considered astute enough and worthy enough to serve in the government ranks, he made ready to set off for the capital city to take the weeklong test. For his journey, his grandmother gave him bamboo kitbag filled with rice balls and dried fish, and his uncles gave him advice about bandits along the way, and coins to pay for his board and keep from the family cache, that was kept in the footed vase.

[Three Chinese, Yuan Dynasty, Ying Ch'ing wares: footed vase with straight rim (uneven glaze color and foot slightly warped), bottle vase (stains) and small jar (no top and minor flaws)] But before Shin left, his father reminded him: "Knowledge is the key to happiness and success. You have learned much, but not enough. When you come back, do not expect to ride on your complacency."

His grandfather, equal in his sternness, addressed him: "All men are brothers. But you must be commendable enough before you can think in conditions of world citizenship."

Although the trip took many days, and there were many exotic things to see, young Shin did not notice the beauty along the way: the carved dragons in the temples, or the birds in the trees throughout the countryside and towns.

[Chinese, carved brownish-tan hardstone archaistic bird-form vessel with dragon and flange designs (chip)] His thoughts were full of Confucius's teaching and ethics, and the unrelenting effort it would take to acquire that knowledge. It was not of the slim girls, offering cool water from their dark clay jars near isolated wells. [Large, Chinese Jin Dynasty, Honan glazed jar of good form and with much iron-rust coloration all over (minor hairline to rim)] Once in the capital, Shin went immediately to the place of the exam. He was given a cubicle in which to write his answers and a rush pad on floor to sleep on when his energy waned. For seven days and seven nights, he wrote his answers on the thin, bamboo paper, and did not leave the proximity of his desk until the test was declared over. It would take over a month for the scores to be decided, so Shin rented a room with other scholars in a widow's house.

While the other young men used this opportunity to be entertained by graceful dancers, who waved their streamers like sea anemones: Shin did not

[Large, Chinese Han Dynasty, Sichuan pottery figure of a dancer (repair to arm, base and possibly neck area), good detailing to face and clothing] And, when one youth stared at him under the porch lantern longer than was seemly, Shin did not return those bold looks, and walked away.

[Pair of well-detailed and carved, extremely large Chinese, dark green bowenite lanterns with openwork good luck and dragon designs on elephant bases (small loss to top of one base)] At last, the marks were released in a formal ceremony and read by a representative of the emperor and empress. [Pair of well-detailed, carved and stained, Chinese ivory figures of an emperor and empress seated on thrones (minor splits to bases and loss to one hat finial), wood stands.] Shin had placed very highly among all the capable aspirants. He returned a mandarin in the service of his village as a water engineer, overjoyed to share his triumph with his family.

However, when he arrived at his farmhouse, all had changed. The sheep, goats, oxen and horse were lowing in pain; the chickens were silent. He did not see his grandparents, his father, his uncle and their wives and children. He ran to the village to ask what became of them. But when he got to the village, the same eerie silence met him. There was the smell of decay and the smoke of many spontaneous pyres. Finally, he went to the family crypt and found his father placing the last tomb brick over his grandmothers body.

[Massive and quite rare, Chinese Han Dynasty, grey pottery tomb brick with tao tieh and ring appliqu and elaborate impressed crane, owl, leaf, geometric and processional designs (small chips and possible minor repair)] Shin's fathers last words to him were: "Remember the slip prunus branch around your mother's vase on the anniversary of her death."

Cholera had taken the region swiftly and almost completely. There was no one to care for the animals or plant the fields with grain and soy. There was hardly enough money to gather in tribute to pay his government salary, so Shin for the first time, worked in the fields. Except for a young girl who did his laundry and cooked his meals, he was alone in that large house for many years.

Eventually, the land re-populated, and Shin donned the distinctive buttoned cap of the mandarins, and began his work as a civil engineer. From the abstract of academic preparedness, he learned the task-focused skills of his profession, and became excellent in this capacity. He grew his nails long to symbolize that never had to do a bit of physical work again, and he met regularly with the other administrators of the land to speak at great lengths about the paternal benevolence of Confucian authority.

[Pair of rare, well-modeled and detailed, Chinese Northern Ch'i Dynasty, painted pottery standing figures wearing long red tunics and small hats (usual repair to one), much original pigments remaining to both.]

Many young girls came to labor in Shins home, but all of them were left untouched by their master. As regularly as the prunus branch Shin put near his mother's vase on the anniversary of her death, and his birth, matchmakers came to offer their services, but none could interest him in an arrangement of marriage. The only female company he kept, was the figurine of a court lady, that was given to him by the regions officials for years of good service.

[Extremely tall and very well-modeled, Chinese Han Dynasty, painted pottery court lady wearing long draping red robes (crack to base and some minor repair)] Then one night, Shin had a dream. He dreamt of beautiful birds, flocks and flocks of them filling the sky, creating a straight line from miles away. [Well-carved, Chinese pale green and white jadeite birds amid lotus group, small areas of apple-green coloration, on carved wood stand with lotus motif.] But when they finally reached him, their formation stopped and they all dropped dead to the ground. This disturbed Shin very much, and he was distressed for many days. Afterwards, he did not go to a fortuneteller to interpret his dream. He knew all along what was expected of him. Thus, after a week, he married.

Shin had told the matchmaker, he did not care about his future wife's dowry, or the status of her family, or her beauty, or her docile malleability. His only requirement was, that she was healthy, and well suited to giving birth.

So after fulfilling her three-month probation period, Shin summoned his wife to his bed with these words: "I will now accept you as member of my family and will allow you to participate in our ancestral sacrifices. Then after you have given me a son, I will never impose myself upon you again."

Nearly nine months to the day of those words, his wife gave birth and died for her efforts. When Shin saw his daughter, he told the midwife to employ a wet nurse.

"Keep her alive," was all he requested of the woman, and the subsequent nanny that raised her.

Shin gave his daughter the name Ling, and then completely forgot about her. But Ling could not help but love him, even though her father never looked at her, never caressed her rosy cheeks, or spoke to her when she served him sweets and tea in the garden.

[Old, English "ironstone" oval platter with transfer pattern of a "Chinese" figure in garden landscape design .] But she loved the way her father attended the ancestors and her grandmother's vase, and that he would recite the words of Confucius aloud, when she sat at the rug by his feet.

[Two Sino-Tibetan wool rugs with figural designs: lohan on yellow-orange ground (minor stains), approx. 2 1/2'X 3 1/2'; and human "skin" on navy-blue (minor wear), approx. 2 1/2'X 3 1/2']

"Propriety and self-discipline are gotten by observing ceremonial forms," he repeated to himself, prior to kowtowing before his family shrine.

When Ling was eleven, with her nurse, she made a discovery on their way to make a special purchase from the salt traders. In the gutter, she found a newborn infant, screaming loud enough so even the oil in the market stalls shivered.

[Antique Chinese (possibly Jin Dynasty), brown glazed covered globular jar with carved linear designs and two loop handles at the neck (chips to rim and cover).]

Many people just walked by the baby, and did nothing, except for one kind soul, who covered his body with a large leaf, which was not large enough to conceal that his right leg was shriveled below the knee.

The previous year, nomads on horseback from the far north, had swept into mountains above Ling's home, taking loot and captive slaves.

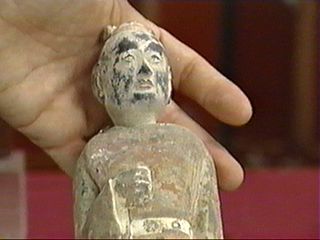

[Massive, Chinese Han Dynasty, seated painted pottery horse with removable head (flaws and some repair), open mouth, well detailed.] Some girls managed to escaped, but not without the legacy of their internment. Banished from their homes, they staggered to the lower valley floor, where they had their children, and then abandoned them. This was such a child, and with the shame of his mother, and without strong legs, he was useless and unwanted.

The foundling was still gray from the placenta, that had not been rubbed off his tiny form, when Ling presented him to her father, against the protest of her nurse.

"Here, father," she said to him, " a son, at last, to serve you in the spirit world."

Shin was about to say: "He will not be worth the rice to keep him." But he did not. He looked at his daughter holding the wailing baby with the misshaped leg, and his heart softened.

"Keep him alive," were the words that echoed from him once again.

Kung, the foundling, was kept with the chattel below the house, where he slept with the fowl and the pigs.

[Chinese, silver gilt mirror with repousse scrolling lotus designs, set with 18th Century, antique jade plaque with openwork fowl and lotus, 19th Century grey dragon-headed belt buckle on handle and small jadeite and gemstone cabochons.] Like the house and land, Kung was considered just another possession, and like the crops on the land, he was considered affixed to it.

But Ling had no prejudice towards this orphan. While Kung was still an infant, she chewed his food before passing them into his toothless mouth, and slept with him every night, after her father had gone to bed. Later, she taught him manners and reverence for his betters. She cared for him, giving him all the love she had never received from her taciturn parent.

Kung grew to be a healthy boy, but even with his crutch, he could not even keep up, dragging his disabled leg after Ling, as she gathered the fatted geese from the fields. Kung had tried to do everything else Ling did, but he was not allowed to place fruit on the family shrine, but did so just the same, when Shin was not there.

[Antique, Chinese white porcelain globular vase of fine form with very well-incised fruit and cloud designs, 18th/19th Century .] Nevertheless, clever as could be, Kung learned from inference his numbers and characters, as he sat with Ling on the rug in her father's study.

"One day, father will formally adopt you," Ling explained, "and when he is gone, you will feed his spirit, so he will not be a hungry ghost.

"Yes," Kung agreed, "and I will seek his protection and pray for prosperity."

For the last three years, the rains did not come, and there was not enough water in the river to irrigate the adjoining plots, or reserves in the ground to fill the wells. Shin was beside himself in this emergency situation, organizing great groups of men to disperse what little water there was left to dampen the crops and satisfy the thirst of the people. But in his exertion, he grew sick and began to die.

On his deathbed, Shin called the matchmaker and arranged a hasty marriage for his daughter.

"They will not treat you badly with all that I will leave them in your dowry," Shin told her." You will no longer be a part of this family, Ling, but you will always be my daughter."

Ling pleaded with her ancestors not to let her father die. She removed all restraint, and wept over Shin's body, her long black hair covering her face and his.

"Father, father, not yet," she cried. "Not yet."

When Shin was no more, a hundred black crows filled the sky, darkening the light, and deafening Lings ears with their offensive calls of "caw, caw." They had come to pick the flesh of the hundreds of people dying for want of food and water.

In her anguish, Ling cut her hair with a kitchen knife, and blackened her face with sooty ash. Just as distressed, Kung threw himself into the dirt, and beat his breast, and tore his clothes. Afterwards, they were too weary from crying to even speak to each other.

Day after day, Ling tried to feed her fathers spirit with what she could find for herself, but there was so little. The land was shrived and dry, and gave nothing. Kung himself grew weaker and weaker until there was little on his tiny bones.

After Ling's period of mourning, the matchmaker and her future husband's uncle came to collect her. She did not want to go, and leave little Kung, but she would obey her father's final wish.

When they were alone on the last night, she told Kung: "You are like precious salt to me."

Kung did not understand what was happening. The next morning Ling did not turn back to Kung, or slacken her pace. Kung tried to keep up, but he was not strong enough to hold onto the hem of her gown, that he grabbed as she walked from the farmhouse. Hobbling up the road after her, he found in his path, the delicate fan Ling had recently dropped, and the hardstone vase of her grandmother that was hidden in her sleeve.

[Well-carved, Chinese lavender quartzite figure of a celestial beauty holding a fan (head re-stuck and small chips).] The journey to Ling's new home took 10 days. She passed by villages where her distant relatives had once lived, but they had all been killed during the last epidemic. If there had been one male relative left, her father would have adopted him, but there was not. The crows stopped scratching the dust when she passed, taunting her with their shrieks.

When she arrived at her new husband's house, she was exhausted and dirty. Something flew past her face. It was a bat, flying up to the clouds.

[Three antique, Chinese Famille Rose enameled porcelain bowls: florals; bird and florals and bat amid clouds (some small flaws to each); two late 19th Century and one circa 1900.]

Ling wore a red gown, and her face was covered with a heavy veil, when she was presented to her husband. The proceeds from the sale of the farm and house, a large set white porcelain plates with indigo birds, and the rest of her family's valuables, that were not sold for food, were placed at his feet.

[Group of thirty-one, South China, late Ming Dynasty, blue and white porcelain plates with stylized bird-like design (glazes degraded and other flaws), from an undersea excavation off the coast of Indonesia.]

After the ceremony, the first wife brought Ling into the wedding chamber; her husband barely looked at her face.

"You are young," her husband, Chang, said to her. "You come from a good family, and have been a fair trade in marriage. Why has your father made such a match for you?"

For the first time, Ling glanced up shyly at her husband. He was very fat, and suffering from gout; eating sweet beans from one of the jade coupes from her trousseau. [Antique Chinese, greenish-blue glazed porcelain coupe of good globular form, Kang Hsi mark but 19th Century]

Gracefully, he rose up on one of his haunches, and let out a burst of gas.

"I have enough wives and many children," Chang continued. "I have concubines to suit my every mood. So why did your father, turn you from your home, and seek me out for this marriage?"

Ling did not answer him, and returned her gaze downward.

Suddenly, Chang cried out: "Aaaaaaaiiiiiiiiiiiii!"

He held his ears and moaned: "The sound, the sound. Its like the piercing calls of crows.

Aaaaaaiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii. Why do my ears pound so?"

Ling hesitated, and then stepped near him.

"Is there anything I can do, sir?"

"No, no, just get out," he wailed, and wavered her out of the room.

The other wives and concubines had not set a bed for her, so she slept at the foot of her husband's door. In her dreams, the crows and the animal heads on the door fastenings chased her through her fathers fields, picking at her heels.

[Pair of large and heavy, antique Chinese wood doors with elaborate iron hardware with animal-head ring handles and floral and boss designs (some old flaws).]

Ling had married into a very rich and connected family. Their home was an elaborate compound with many wings and many suites. There were enough rooms to house their many possessions, and food enough so she never went hungry. But it was closed to the world; a keeper watched the gate. The women of the household sent young male messengers to do their shopping and bidding. The only natural world she saw, was the garden in the center courtyard with its goldfish pond and delicate plants.

[Set of three, Chinese carved spinach jade or green hardstone models of goldfish, wood stands.] Ling visited her husband once a month when it was her turn to join him at night. Each time, he asked the same question of her, the mystery of her fathers decision. And every time before either could answer, a terrible shrieking came to his ears, and she was jostled out.

With nothing to do, Ling became curious about the many musical instruments displayed on wooden stands. [Set of ten, finely executed Chinese carved agate and hardstone miniature models of musical instruments, wood stands for each.]

She found concubines who knew how they were used, and from them, learned to play the lutes and flutes quite proficiently. It then became her practice, to secretly venerate her father with food and a pinch of salt, and to dedicate her songs to him, as she made her soft and melancholy music.

When Chang heard that she could play, he ordered her to entertain him. He was much pleased by her ability. But when he reached for her, the same awful sound of crows cawing punctured his ears. So he learned to listen at a distance, and not ask anything more.

Years passed this way. Aside from Changs daughters, Ling was the only maiden in the house. Her music became sadder, and more pure, and all agreed, even more beautiful. For the first time in her life, there were people enough to eat from all the plates, that only she and her father had used, and with so much company, she was made content to a degree. But she had a sickness in her heart that would not go away. She asked the doctor who visited, why she felt so ill.

He looked at her tongue, felt the top of her head, checked her earwax, and sniffed her armpits.

"You are suffering from a separation from your love," was his professional opinion.

"But I have never known any man," she protested.

The doctor shook his head, and took out a mandrake root from one of the many drawers of the family medicine cabinet.

[Attractive, older Chinese black lacquered elm wood medicine cabinet with numerous drawers and good hardware (minor flaws)]

"Grind this up, and drink it with your tea," he said, and gave no further explanation.

This plump root, the shape of a virile man with strong arms and legs, did no use. Ling still had a malaise that would not leave.

It was the time, when her father would have put a slip prunus branch at the base of her grandmothers vase, when barbarian horsemen from the barren steppes came to loot and ravage the land. With little effort, they broke through the protective gates of the compound, and killed Chang and the older wives and concubines.

[Large and well-modeled, Chinese early T'ang Dynasty, pottery figure of a standing warrior with animal-mask design shield (some possible repair), some traces of pigments remaining.] Ling and the rest of the women and children were herded together, bound and shackled, and led behind their captor's war wagons, that were filled with stolen riches.

For twenty years, Ling had lived in the house of her husband, bricked up like a prisoner. But now, even tethered to other living spoils, at last she felt free, walking before her shadow, which never fell on the same spot twice, and traversing the Great Wall, where it was secretly penetrable.

One night, when burying a fire, Ling came across three large, strange, rock-like objects of pre-historic birth.

[Rare, large cluster of three, Sauropod species dinosaur eggs, excavated in Honan Province.]

She knew immediately what they were, and called the guard to tell him of her unearthing.

"Tell your master when he joins us, that I have made a great discovery that will make him renown throughout the land," Ling instructed.

"Foolish woman," he scolded. "Do you think our Mighty Khan, would deign to hear about your irrational discovery?"

She did not want to argue with him, so she hid her treasure deeply in the dung cart, where she and the other women stored the dropping of the horses that was used for fuel.

With regular intervals, others joined her cavalcade, carrying more booty from raids across the empire: persimmons, roses, gunpowder, porcelain, sandalwood, jade, pearls, and silk. There were decorative furnishings like the carved screen from a lesser warlord's home, that still had the imprint of his bloody grip.

[Finely refinished, old Chinese elm wood four-panel screen with superbly carved openwork floral and animals in landscape designs (minor flaws and small repairs)]

More women were added to the troop, blondes from the frozen north, towering over their warders, and dusky girls with braids like hemp, whose every step was a seductive dance.

The caravan stopped when they reached the land of high elevation, sparse rainfall and rolling grasslands, where there was no sign of life, except the occasional great bustard, and herds of flee footed gazelles that left clouds of dust. When the signal was given, the company set up the hide yurts, and corralled the animals that were not to be slaughtered. A feast was made in preparation for the arrival of the most powerful khan.

The Mighty Khan was proceeded by his finest warriors, whose beaten metal shields glowed in the sunlight.

[Very well-modeled and painted, Chinese Han Dynasty, pottery group of an equestrian with groom (some usual repairs), groom on lucite stand; much pigments remaining to both.] No trappings distinguished this man as the leader of all leaders. A simple strap held his quiver; a reflexive bow of plain birch crossed his broad shoulders, and a short, unadorned knife lay ready at his hard waist. But there was something wild and menacing about his imposing comportment and physique, for even riding, without touching the bareback seat of his stocky pony, he seemed organically adhered to it.

"He never steps off a horse," came the murmurs from the crowd." He does everythiny all men would do on the ground. He is always ready to fight and like a horse sleeps upright."

Ling looked up to inspect the Mighty Khan's features, they were very fine and regular, but the long scar from his left eyebrow down his cheek, kept his expression cruel and disdainful.

It was the custom of this tribe, to give the Mighty Khan his first choice of captured women. But he could only keep, those he would clasp and penetrate. Ling found herself trying to make herself as presentable as she could for him, though her skin had become browned and weathered by the sun, and her hands coarsened from work. Still, a life of music and chastity had kept her youthful looking and pretty, and her limbs had grown strong through the extended

trek.

When Mighty Khan saw Ling, he steered his way from the others, and towards her in the line of assembled women. A cold cloud covered the sky, and brought a light rain. Through the drops, Ling's eyes burned with passion.

"My lord, a favor," one of the soldiers asked. He was the guard that Ling had reported her rock-like discovery. "You have said that I may have my choice of maidens for having given you my utmost."

Without a second word, the Mighty Khan walked passed Ling; and the soldier, Xeng, took her by the arm, and away from the others.

During the feast, Ling kept Xeng's wine cup filled, and only when the flames of the fire that separated them, were high, stole a look at the Mighty Khan, who was above all of them, still on horseback, watching the saturnalia, maintaining the side of his face towards her that was torn and disfigured. Even so, Ling felt strong music forming inside her, which for the first time was happy.

Many hours of toasts and song were made to the Mighty Khan: "the bravest lion of the taiga forest, permanent pasture and true desert."

[Pair of Chinese (probably antique), brown glazed models of lions with brocade balls (chips)] Afterwards, Ling shouldered Xeng's drunken weight through the bodies stultified with drink. A frosty wind blew from the pure lakes. At the open flap of their yurt, the Mighty Khan on horseback waited.

"As your Khan, I am owed first rights," he pronounced.

Xeng's response was to fall down to the ground, and heave up his violent reaction.

Ling ran, sometimes tripping over the fallen bibbers. The Mighty Khan followed, indenting his horse's hooves over the unfortunate. When Ling spied a free mount, she leapt on its back, and into the steppe's dark night. She beat the flanks of the shaggy pony with her heels and hand, riding it hard as if on campaign.

"My father, my ancestors, help me, help me," she cried.

The Mighty Khan let her give chase; he cut in front of her in a lazy "S" pattern, and rushed her from behind, steering his horse so close, the animals were nearly mating.

It was obvious, she was no match for him, and when he was ready, he grabbed her hips, and seated her in front of him. She struggled: kicking him, using her fists on his thighs, and elbowing his stomach, her agitation imperiling both of them with falling. Still, the khan kept her close to his body gently, and never struck back.

When she was all out of fight, he turned his horse around, and trotted back to the camp.

"Tomorrow night be ready for me," he said, letting her slip to the ground in front of her yurt.

To Xeng, who had remained, he warned: "I have not taken her; so shall you not."

The next day, before she went out to tend the goats, Xeng struck Ling on the soles of her feet, and upon the head, where her hair hid the marks; he knew how to serve his fury without detection.

That night, the Mighty Khan pulled Ling to his horse, and once again, seated her astraddle in front of him, so she could not see his face.

They road silently, and without following a discernable course, varying the pace of the horses gait, their bodies constantly, inadvertently caressing. Soon their breathing synchronized, and so did the beat of their hearts. At the end of their ride, the Mighty Khan let her off his steed once more unsullied.

This became a pattern for Ling: days of punishment, and nights of pleasure; the two men fighting over her acquiescence, over the long winter. Without rest, at the extremes of sensation, and with no placation in sight, Ling was transformed. For her, this feeling for her Khan was a matter without thinking, exhortation or explanation. It was boundless and absolute, a Taoist expression of mystical and effortless perfection.

[Chinese, silver gilt mirror with Taoist emblems, set with an 18th Century carved celadon jade oval plaque with openwork fowl and lotus designs, a 19th Century celadon jade dragon-headed belt buckle and with jadeite and gemstone cabochons.] On a night, when the large orange moon laid low in the sky, Ling made a bold move: she turned her seat on the horse, faced the Mighty Khan, and gently stroked his wound.

"I am touching your strength," she spoke, and pressed her lips to the deepest part of his score.

The next day, the Mighty Khan with Xeng and the others, began preparations to vanquish new lands and other peoples.

"I will bring back anything you wish," the Mighty Khan told her.

"With you gone, I will be in a wilderness, and shall miss the taste of salt," she answered.

Throughout the year, Ling thought of the Mighty Khan; of her figure merging with his and the horse, in reflection of a mythical being older than China itself. As she drove the flocks to fresh meadows, her mind was filled with all the lovemaking that had been deprived her, and all the love amassed within her, through the years that knew no expression.

[Group of eight, cold-cast "bronze" composition erotic "okimono" of mostly couples in various amorous embraces ]

When the Mighty Khan returned, he presented Ling with rare vases filled with salt, gotten from the high Himalayas. Two ancient, Ban Chiang pottery jars: Early Period globular and Late Period red on buff pedestal-type (flaws and repairs) At the sight of the gift, she wept and wept.

"Because of you, I have nearly forgotten the love, I had for a little one, that was my child and my brother," she sobbed. "If I love you, I cannot love anyone else."

Hearing her audacious confession, her intended, Xeng, pushed her down to the ground.

"What was the discovery you made," Xeng demanded of her, "that you have so clearly tried to conceal?"

Ling was too frightened to do anything, but plainly speak the truth.

"I have uncovered the eggs of a dragon," she confessed of the jurasstic remains.

A hush went through the crowd.

Xeng confronted the Mighty Khan.

"Is it not your law, that anyone who conceals plunder, shall die?" he asked.

But as Xeng complete the last word, the Khan leaned forward, and neatly his head from his neck.

Ling screamed; and her screams brought down a thunderstorm with lashing rain.

A week later, when the storm was over, Ling went to the Khan with the dragon's eggs she had hidden.

"Will you make my death swift?" she asked, knowing the order of the people demanded her extinction. There was remorse in the voice, because she had roused the khan to kill on her behalf, and she blamed herself absolutely.

"I will make your death a lingering occasion," was his even response.

"I hate you," she spoke.

"How much?" he asked.

"As much as I love you," she divulged.

He took her on his horse once more, and together they rode far away, to where a large rock stood by itself. On this rock, the gifts and sacrifices from other travelers were presented. To the offerings already displayed, the Khan added his own: the phoenix on the hardstone vase.

"I tried to follow you, but with only one good leg, I could only drag the other. And soon, it became bloody and festering," he began. "As you taught me, I prayed to your father's ancestors, and promised to do anything to amass a fortune, to dedicate it to them, if only I could be with you anew. I suffered constant deprivation, and had many acquaintances with near death, but somehow, I survived long enough to be kidnapped by these roving tribes, and I learned the way of the mounted attack. From that moment on, my legs ceased to exist, or be anything more than a way to keep me gripping my horse, and moving forward.

"I overturned the world to find you, sacking what remained to continue my search. In the end, I knew I would cull you from all others.

"It would seem, I had became antithetical to what your father resembled: uncouth and irreverent; half beast with no need for logical explication."

He took her face, and tipped it for a kiss.

"I was the sea returning to rain."

"But when I left, you were not more than six. How could you remember me?" Ling asked, amazed.

"I began to hear music that resembled the sadness of my loss. It became louder and louder, so I knew I was on the right path to my destiny. When I saw you, the music stopped, and I knew that your father had preserved you, and had guided me rightly."

[Chinese, carved aventurine quartz group of two beauty musicians, wood stand.] "My child, my brother," exclaimed Ling.

"Your lover, your husband," the Mighty Khan corrected her. "Your murderer."

"How will you kill me?" she bravely inquired.

"I will love you to death," he stated.

He rode with her as one, until the dawn opened the bright, blue sky. He loved her every night without the arts of civilization, and armed by a mandate of heaven. He loved her knowing, as her father had known, she would perish in childbirth, as her mother and grandmother had done before her. He loved her alone, with only the company of winds, and in the shadow of dragons. He loved her like that, until her form got too bulky to balance them both on the horse's broad back.

When it came Ling's time, for the first time in years, the Mighty Khan stepped onto the ground. Unbalanced by his wither leg, he knelt beside her, gathering the blood from her womb into tiny vials.

[ Group of ten, well-hollowed Tibetan agate snuff bottles of various sizes, most with agate stoppers (one coral and one "goldstone")] He buried her with what was left of the fan, that she had dropped for him to find those many years ago, and sprinkled her lips with the salt of his tears.

When their son grew old enough, he placed a slip prunus branch by her vase every year. And when he became the bravest lion of the taiga forest, permanent pasture and true desert, he gave her a different altar on every new journey he began in her honor.

The End Copyright Yvonne Ignacio 2000

ANTIQUARIAN TALES Return to Books and Other Writerly Works |